Apr5

Author Archives: romeojennifer

Apr5

Cinderella as a Text of Culture

It is impossible to think of Cinderella without thinking of the 1950 Walt Disney animation film and the timeless images we’ve all grown up watching. In any case the 2015 Disney release of Cinderella proved how durable the story is. Even a director such as Kenneth Branagh couldn’t resist the appeal of this quintessential fairy tale. The live-action Disney remake of Cinderella boasts an exceptional cast starring celebrated stage and screen icons as well as and raising stars tapped from today’s best television.

Even if you have miss this last version of Cinderella, I am sure all of you would have at least once in your life watched one of the many audiovisual versions of the tale produced for the tv and cinema.

But was Cinderella originally created for the screen?

Cinderella belongs to the literary genre of fairy tales. In such a field the autorship of the tale is likely to turn into a debatable point when you consider the rich oral traditon behind it, the issue of text and illustrations and the relationships to its many other different versions. As regards the many existent Cinderella fairy tales, three written texts particularly, are to be taken into account for the making of this well-known story: Giambattista Basile’s “La Gatta Cenerentola”, Charles Perault’s “Cendrillon ou La Petite Pantouffle de Verre” and the brothers Grimm’s “Aschenputtel”. Accordingly, the majority of the subsequent authors, who reworked the tale of Cinderella, credited the above- mentioned texts as their basis. The three texts present both affinities and differences among them but they equally include some patterns, symbols and values that ensured the fortune of such a fictional character through time and space. There are countless of children as well as adult version of the Cinderella sort of story that can be found throughout lots of different regions, as well as in different time periods (Anklet for a princess: a Cinderella story from India, Sootface: an Ojibwa Cinderella story, Cinderella an Islamic fairytale, Gioacchino Rossini’s Cenerentola, ossia La Bontà in trionfo, Sergej Prokof’ev’s Cinderella, Roberto Innocenti’s Cinderella etc..). The fact that this fairytale has also been reworked for ballet, opera, television and cinema (Gioacchino Rossini’s Cenerentola, ossia La Bontà in trionfo, Sergej Prokof’ev’s Cinderella, Pretty Woman, Ever After: A Cinderella story, A Cinderella Story etc…) also shows the passing on of the character of Chinderella throughout different textual genres indifferently .

Where then does the appeal of the Cinderella tale really lie?

A series of key-elements can be eventually considered to give explanation for the extraordinary amount of versions, translations and rewriting of Cinderella. Lots of issues are dealt with in this particular tale; issues that in the last analysis, reveal themselves as being at bottom of Western world culture. Class, gender, expected behavior are mixed together within the text. But it treats the issue of family as well. All these aspects make it a fundamental text, by which investigating some of the conflicts inherent within our Western world. And this is exactly the use that lots of storytellers made of Cinderella.

Briefly, Cinderella is the story of a girl, whose life changes when her widower father remarries a cruel women, who dislikes her. The new stepmother and her daughters mistreat Cinderella, turning her into a servant in her own house soon after her father’s death. The heroine, is put through the wringer, but after some key events to the framework of the story (the ball, the loss of the slipper and the related shoe-test episode)- and due to the aid form some natural or supernatural beings (animals, plants, the fairy godmother or the death mother’s spirit), she gains back a rightful and suitable place to her character, merits and birth.

The story, as it has just been roughly drawn, contains all the issue named before. Even though details might change among the diverse Cinderellas presented, the presence of the basic motifs is recorded anyway.

As regards the class standing, the heroine regularly moves from a higher to a lower position and vice versa, providing evidence of the importance of one’s social background, as well as showing rights and duties expected of everyone according to that: Cinderella isn’t worth to attend the snooty happening because of the situation of social inferiority she is trapped in, but disobeying her master’s order, she manages to go there and at last she gets married to a wealthy man, once her real high class status has been revealed and restored.

In connection with that subject, wealth is also broached throughout Cinderella’s stories. The heroine can’t take part in the event, not only because of her lowered class status, but also because she doesn’t own the requested goods to do so. It’s not without reason that some scholars recognized clues of capitalism within the text, owing to its stress on material goods and money as fundamental values in Western societies.

Outward appearance is another basic point dealt with in Cinderella. Beauty is actually one of the heroine’s most important characteristics, and it is often compared with her stepsisters’ ugliness. The worth of beauty is also plain within the text, since the female triumph in the desired male’s heart is due most of the time to the woman being all dressed-up and so even more attractive to the man’s gaze. The spread of dominant standards of beauty set upon females by society could be easily pointed out within the text.

This particular aspect allow to introduce the gender issue, that is unavoidably touched in the tale. In effect Cinderella has always been seen as the prototype of femininity. Being mostly depicted as gorgeous, good-hearted and subservient, numerous interpretations have been made as to the fact that most Cinderella tales present a male-dominated point of view on society. The housekeeping, that is constantly delegated to such a female protagonist, together with the accent that the story puts on the meaning of marriage in a girl’s life, strengthen the gender conflict. However, not all Cinderella figures have been depicted as being passive and completely subject to other people’s will. A lot of stories present a proactive sort of heroine who tries to help herself rather than remain helpless. This point paves the way to consider the contrast between vitality and inertness inherent to the Cinderella text.

As a final point, family dynamics are a central component of the story. The traditional character of Cinderella is commonly associated with a orphan daughter, both neglected by her father and ill-treated by her new step-mother. Parent-child relationships are absolutely central to the story itself, as well as those concerning the bond of sisterhood, that in most of the texts becomes a bitter rivalry between Cinderella and her step-sisters.

The above-indicated aspects, are more or less latent within the varied Cinderellas presented, with copious changes in them according to the case.

To sum up, the contrast between the acceptance of femininity as imposed by men and its refuse by the woman who is in search of a personal definition of self becomes the focus of attention of Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman. The complex mother-daughter relationships emerge as being the dominant factor of Angela Carter’s “Ashenputtle or the mother’s ghost”, the class boundaries are an important subject matter throughout the brothers Grimm’s text. In addition, the good-behavior as quality of every aspiring lady-to be is visible in Perrault’s Cendrillon, as well as the stress on the heroine’s great beauty in Disney’s film recreation of the tale. The contrast passiveness-liveliness is a core attribute of Basile’s La Gatta Cenerentola as the pained sexuality constitutes the main topic of the various male Cinderellas in the examples of GLBTQ literature available.

All things considered, Cinderella lent herself to a number of different interpretations. It is exactly the pliability of Cinderella sort of story, her being a combination of relevant aspects that fascinated compilers, storytellers, writers, directors and composers, who met with the text, each reflecting his/her own inclinations. As a result, generations of readers/watchers have been enchanted by such a miscellany of texts.

Image Credit:

Cinderella 1950, Cinderella 2015 taken from Google Images

Apr4

Where are we heading?

“In advanced modernity the social production of wealth is systematically accompanied by the social production of risk”.

With this statement, Ulrich Beck opens the first chapter of his most renowned work “Risk Society, Towards a New Modernity”(1986). It has been a long time since then, and yet some of the German sociologist’s pioneering considerations contained in that book seem to be still valid today.

With this statement, Ulrich Beck opens the first chapter of his most renowned work “Risk Society, Towards a New Modernity”(1986). It has been a long time since then, and yet some of the German sociologist’s pioneering considerations contained in that book seem to be still valid today.

In what Beck refers to as ‘modern’ society there has been a shift from a ‘wealth-distributing’ society to a ‘risk-distributing’ one as a product of the modernization process itself. The staggering techno-economic development and its mass production of goods, Beck claims, has unfortunately led to an uncommonly production of “bads” or, to put it differently, of risks.

“Risks” – the author promptly clarifies – “are not an invention of modernity” and yet, there are substantial differences between past risks and modern ones. Risks were once perceptible, whereas today most of them are undetectable. Moreover, in the past they were due to a dearth of technology (especially in sanitation), whereas in our day they ascribe to overproduction. In short, Beck maintains, “they are a wholesome product of industrialization, and are systematically intensified as it becomes global”.

The author continuously insists on the global threat they represent for all life on Earth. Owning to the very “nature” of the risks here examined – namely radioactivity, toxins, as well as pollutants in the air, water and foodstuff- the very notion of calculation collapses.

Risks mostly occur in scientific knowledge about them, the author states, outlining this way the increasing reliance on science for defining them. All we know about risks, he alleges, comes from people with specialized knowledge in certain research areas.

Another crucial point here presented is that concerning the social inequalities connected to risks. On the one hand, some risks, Becks points out, could be classified as class-specific risks, since they can result from the place where you can afford to live, form education and even from the food and beverage you can afford to buy. On the other hand, risks are unevenly distributed between underdeveloped countries and industrialized ones, with the former, so to speak, “purchasing” additional dangers to cope with poverty (here the author hints of the “cultural blindness to hazards”) and the latter “selling” them to be safer (e.g. “balkanization of risks”).

In this sense, the author claims, “old social [as well as national] inequalities are strengthened on a new level. But that does not strike at the heart of the distributional logic of risks”. Because of the ongoing globalization process, “risks display an equalizing effect within their scope and among those afflicted by them”. Risks don’t discriminate between class and nationality. They represent a global threat and therefore worldwide solutions through transnational cooperation are required. “Risk society in this sense is a world risk society” Beck states.

Nevertheless, risks don’t escape the logic of capitalism. “There are always losers but also winners in risk definitions” the author asserts. In the long-run, risks will eventually affect also the people who profit from them. “Under the roof of modernization risks, perpetrator and victim sooner or later become identical” and in this regards, risks involve what Beck calls a boomerang effect.

Another “intrinsic property” of risks is that they “have always to break through in order to be acknowledged”. Only after being socially recognized, they enter the public domain, usually sparkling a heated debate over whom is to blame for the catastrophe.

Going back to the incalculability of risks, Beck adds a further argument by saying that by their very nature modern risks – bear in mind that some of them involve a latency period – require the “sensory organs of science – theories, experiments, measuring instruments- in order to become visible or interpretable as hazards at all”.

In Beck’s point of view, there are no experts on risks. There are too many parties at stakes, especially when it comes to risk assessment. There are different ways to deal with risks, but in the case of civilization’s risks, the author asserts, “the sciences have always abandoned their foundation of experimental logic and made a polygamous marriage with business, politics and ethics”. With regard to risk definition, there is a sort of selection of (im)plausible hazards, which depend both on scientific expertise as well as on what a society recognizes as a risk and defines how important it is do deal with it.

As a final point, Beck argues that as much like inside capitalism, world risk society features a lack of responsibility. “Everyone is cause and effect, and thus non-cause”. It’s the generalized other- the system- the one to be blamed.

Throughout the passage, the author highlights the upcoming threatening component that risks basically express. Quoting directly from the text, Beck assesses that “the center of risk consciousness lies not in the present, but in the future. In the risk society, the past loses the power to determine the present. Its place is taken by the future”. In view of this impending fate, how can society acts defensively if there is no escape from such global peril? Anxiety, fear, indifference, rage, Beck says, are all understandable feelings if one takes into account the uselessness of any concrete measure to cope with modern risks. However, non action is not admissible because behind carelessness risks grow and run out of control.

Now then, do you think that Ulrich Beck’s theorization of risk society could be taken as a framework of reference for the current proliferation of end-of-the-world narratives that throng contemporary cultural expressions? Staying within the domain of audiovisual texts I am sure all of you would have watched at least once in his life, one of the so called ‘disater movie’. Thus, what I would like you to do now, is to watch something so to say ‘offbeat’: a 82 minutes docufilm, that presents a far more frightening vision of the world witout being as spectacular as the blockbuster disaster-movie you are all familiar with: based on real events and plausible conjectures, Collapse by the American filmmaker Chris Smith, explores the theories, writings and life story of a single man, Michael C. Ruppert.

References:

BECK, U. (1992), On The Logic Of Wealth Distribution And Risk Distribution in Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity, New Delhi: Sage. (Translated from the German Risikogesellschaft) 1986.

Image Credit:

Ulrich Beck and Hardcover of the Book: Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity taken from Google Images

Apr4

What do you think history is? Has literature got anything to do with it?

In this article I’d like to talk about the connection between history and literature and to do so, I will focus my attention on the work of a scholar, namely Hayden White, who studied the narrativizing process involved in the recording of historical events. Hayden White is a very important and though controvertial figure in the field of history and literary criticism. In his “The Historical Text as Literary Artifact” (in Tropics of discourse: essays in cultural criticism, 1978), Hayden White critiques what he considers as a “reluctance to consider historical works as what they manifestly are”, contending that history is a verbal artifact, or rather an object of language. He tries to blur the disciplinary distinction between historiography and literature (being the former traditionally thought of as a representation of reality and the latter as dealing merely with fiction) by defining history as “constructed narrative”. In his opinion, history is always a matter of telling stories about the past. Those stories take their shape from what he calls “emplotment”, namely the process through which the facts contained in chronicles are encoded as components of plots. This is a very relevant point insomuch as it both foregrounds the creative action of constructing narrative out of a set of events and draws attention to the multiplicity of stories that an historian could conceivably tell by using roughly the same set of facts.

Hayden White is a very important and though controvertial figure in the field of history and literary criticism. In his “The Historical Text as Literary Artifact” (in Tropics of discourse: essays in cultural criticism, 1978), Hayden White critiques what he considers as a “reluctance to consider historical works as what they manifestly are”, contending that history is a verbal artifact, or rather an object of language. He tries to blur the disciplinary distinction between historiography and literature (being the former traditionally thought of as a representation of reality and the latter as dealing merely with fiction) by defining history as “constructed narrative”. In his opinion, history is always a matter of telling stories about the past. Those stories take their shape from what he calls “emplotment”, namely the process through which the facts contained in chronicles are encoded as components of plots. This is a very relevant point insomuch as it both foregrounds the creative action of constructing narrative out of a set of events and draws attention to the multiplicity of stories that an historian could conceivably tell by using roughly the same set of facts.

In this way he recounts, therefore, the explicit involvement of the historian in creating his personal reconstruction of the past and by doing so, aligning him with the role of the writer.

Moreover, the author identifies four possible emplotments (tragedy, comedy, romance, satire) that historians share with their audiences by virtue of their participation in a common culture. The reader, in the process of following the historian’s account of those events, gradually comes to realize the story he is reading is of one kind rather than another.

The very process of emplotment also requires to make some choices of emphasis and omission that obviously come from the historian’s own preferences. History, he puts forward, turns out to be neither concrete nor exact, but rather an interpretation of events.

The author argues that historical narratives are more closely linked with literature not because historical narratives are fictional themselves but because while trying to make sense of any given historical event historians employ tropes in the very process of “storytelling”. He distinguishes four master tropes, or mode of figurative representation (metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony) which correspond to the four types of emplotments already mentioned. The language in which history is written, he finally asserts, cannot be dismissed. In short, historical narrative does not reproduce the events it describes, but rather tell the reader in what direction to think about them.

In conclusion, White deplores the present state of the discipline and calls for reconnecting history with its “literary basis” in order to allow for the incorporation of theories of language and narrative and thus a “more subtle presentation” of historical events.

References:

WHITE, Hayden (1978), The Historical Text as Literary Artifact in Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Image Credit:

Hayden White taken from Google Images.

Mar17

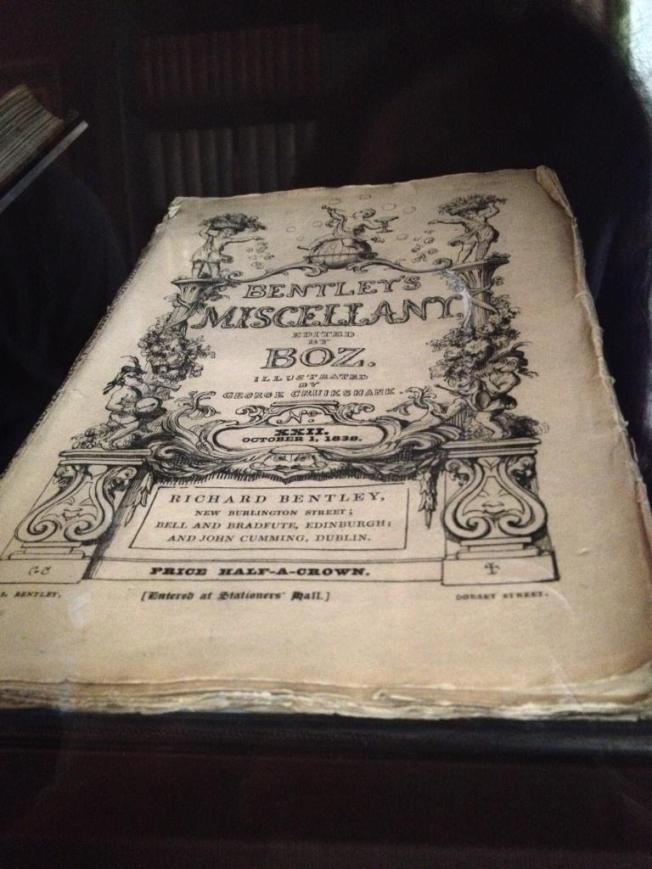

Do you happen to know Boz?

Does this picture remind you of anybody in particular? I really hope it does, but for those of you who can’t recognise this man, he is Charles Dickens, portrayed in 1836 by the well-know artist George Cruickshank.

As you already know, one of the aim of this blog is to give you some tips on British authors and books that I consider important for you to read in order to get a broader knowledge of English literature, so let’s start our ‘literary route’ with the author, whom both in his private and public life and works embodied the Victorian Age.

Today we will deal with the famous Victorian writer, whom I am sure almost all of you can associate to a couple of books, at the very least. Do not worry, I have made up my mind to make Dickens more ‘consumable’ for you, whilst trying to educate you on something that is sadly considered not worth teaching to our students.

Now watch this video by BBC to brush up on Charles Dickens’s biography. It will only take you a couple of minutes to do it and I promise you, you wont’ get bored.

To begin our exploration of Dickens I will provide you with some more information about the begining of his working career that will help us approaching the text that I have chosen for you.

Before becoming a renowed and wealthy writer, Dickens had struggled to make his living (his family financial situation had forced him to live school at a very young age and work in order to support the family). In the late 1820s he undertook a few jobs – working first as a law clerk, and then as court stenographer – until he finally became a shorthand freelance reporter (1828-1833) at the law courts of London. During his parliamentary reporting days he began writing fiction. His first sketch was published in 1833 in the Monthly Magazine. The next year he secured for himself a job at the Morning Chronicle, doing both parliamentary and general reporting, whilst dashing about the country. During that time, he set up submitting other sketches to several London newspapers and magazine (the Monthly Magazine, Bell‘s Weekly Magazine, the Morning Chronicle, the Evening Chronicle, Bell ‘s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle) under the pseudonym “Boz“. The sketches were a resounding success, both with the critics and the general reading public: his career as a writer – and a very prolific one in the many years to come – had officially started.

So now let’s go back to the picture of the young Dickens that I have include in this page. I haven’t picked it up randomly among the many portrait of the author available online. The one that I chose was portrayed by George Cruickshank, an highly regarded artist at the time when Dickens was trying to make a name for himself. But how did the two of them, an artist at the height of his fame and a novice writer got to know each other and work together?

In 1836, Jonh Macrone, the editor of the Monthly Magazine asked Cruikshank to collaborate with Dickens by illustrating those very same sketches appeared between 1833-35. They would be later collected in a volume form (the first series appeared in February 1836 and the second one in December of the same year).

Did you know that almost all Dickens’s books were illustrated; that the author was very fuzzy about the illustrations to accompanying his writings; and that he had a very close personal as well as personal relationships with the artists that over the years provided the images for his own texts?

«Even when his reputation was secured, his sales steady, and his audience literate enough to permit his to publish his text unadorned […], he usually retained the illustrated format clearly convinced, despite the difficulties of coordinating text and pictures, of its advantages to himself, his publishers, his illustrators to a lesser extent and, above all, to his readers».

This accounts very well for the pervasiveness of the graphic element to integrate the textual one within the Victorian fiction and the strict relationships of this particular phenomenon with general book marketing strategies (PLEASE NOTE that still many other Victorian authors didn’t draw upon pictures to match their texts, but for a novelist such as Dickens this was a significant factor in the process of creation and in the total form of his large literary output).

So, Dickens was asked to collaborate with Cruikshank for the making of the two series of Sketches by Boz. For all that I have said so far, it is clear the the modern shape in which we know the sketches is by no means the original one in which they first appeared. Macrone had to pay Dickens the royalities for the previously published sketches and the writer engaged in an extensive work of revision of his own texts, cutting parts, re-writing paragraphs and changing style and punctuation when necessary. Being just an ‘unknown Boz’ at that time, he was obviously flattered by the fact that his texts were to be illustrated by the acclaimed Cruickshank, whom he highly admired. Despite being aware of the indebteness of his texts to the pictures, since the very beginning of their partnership, Dickens attempted to subordinate Cruikshank’s work to his own; this led to a series of misunderstainings between the two that affected the very shape of the work and obviously delayed the deadlines for its publication).

I am deliberately lingering on Cruikshank, because he was the very first artist to illustrate Dickens’s work (7 other more artists would have succeded him over the year), and despite his short and limited partnership with Dickens (apart from the Sketches by Boz he would illustrate just one more novel by Dickens, that is to say Oliver Twist), he is still considered the best due to the artistry of his engraving that integrated perfectly Dickens’s highly visual writings.

But why Cruikshank was selected in the first place to collaborate with Dickens? This was strclty related both to the form and content of Dickens works that was highly indebted to the that of William Hogarth, one of the most successful eighteenth century satirists, whose Cruikshank was considered to be the heir. Besides, given the urban nature of the Dickensian sketches, where the author depicts the everyday life and language of ordinary people in the city of London, the sketches were commisioned to be illustrated by the very same artist that had already produced some engravings for a ‘Life in London’ by Pierce Egan. Dickens, then, didn’t invent the genre of the London sketch, several other texts by author such as John Poole, Theodore Hook and Thomas Hood had been circulating long before the appearance of Sketches by Boz.

Where does the importance of the Dickensian sketches really lie? How can the sketches be assessed in the light of the author’s later production? It is undoubtedly true that the sketches have been underestimated for a long time and only recently their importance have been finally recognised by scholars. Through the sketches, Dickens photographed the life in London as it was in the 1830s. He portaited the different human characters that were the byproduct of the metropolitan lifestyle, or rather, the type of life therein conducted by all those individuals dwelling in London at the particular time of history.

Thus, the sketches, for being partially the representation of Dickens’s journalistic eye and for their being deeply anchored to the time of writing represent a first example of the documentary realism that was to underpin Dickens’s later prose.

References:

COHEN, Jane R. (1980), Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators, Ohio State University Press.

Image Credit:

A pencil sketch of Charles Dickens drawn by George Cruikshank in 1836 (http://photohistory-sussex.co.uk/DickensCharlesPortraits.htm)

Feb25